At 2:38 PM Eastern time on November 22, 1963, CBS News icon Walter Cronkite looked into a television camera, removed his glasses, choked back tears, and informed America that President John F. Kennedy had died. The moment was momentous in its historical nature, but it was also indicative of a cultural reality that has long since passed. At the moment Cronkite announced Kennedy’s death, there were very few places where the average citizen could get their news and information. A miniscule number of television channels, various newspapers, or radio channels were the only destinations where people could learn about the events of the day. This resulted in a metaphysical reality that was cohesive and linear. The ‘truth’ was what you and your neighbor saw or read in the news. This wasn’t the result of some naive trust, it was simply because the overarching narrative of information was unchallenged, and therefore seemed self-evident.

However, it is also true that citizens at the time did maintain a level of civic trust with their political leaders. When past president’s like Franklin D. Roosevelt, or Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke to the nation, Americans generally felt like they were hearing measures of truth. This trust began to erode in the years after President Kennedy’s assassination, and the Vietnam War era presidency of Lyndon Johnson. Yet according to the Pew Research Center, in the year after Kennedy’s death (1964), around 77% of Americans still maintained a feeling of public trust in their government. The same could probably be said for the news media of the time. When figures like Walter Cronkite spoke, the information they conveyed was regarded as true. Even Cronkite’s signature end of broadcast catchphrase, ‘and that’s the way it is’ signified an honest, truth oriented certainty.

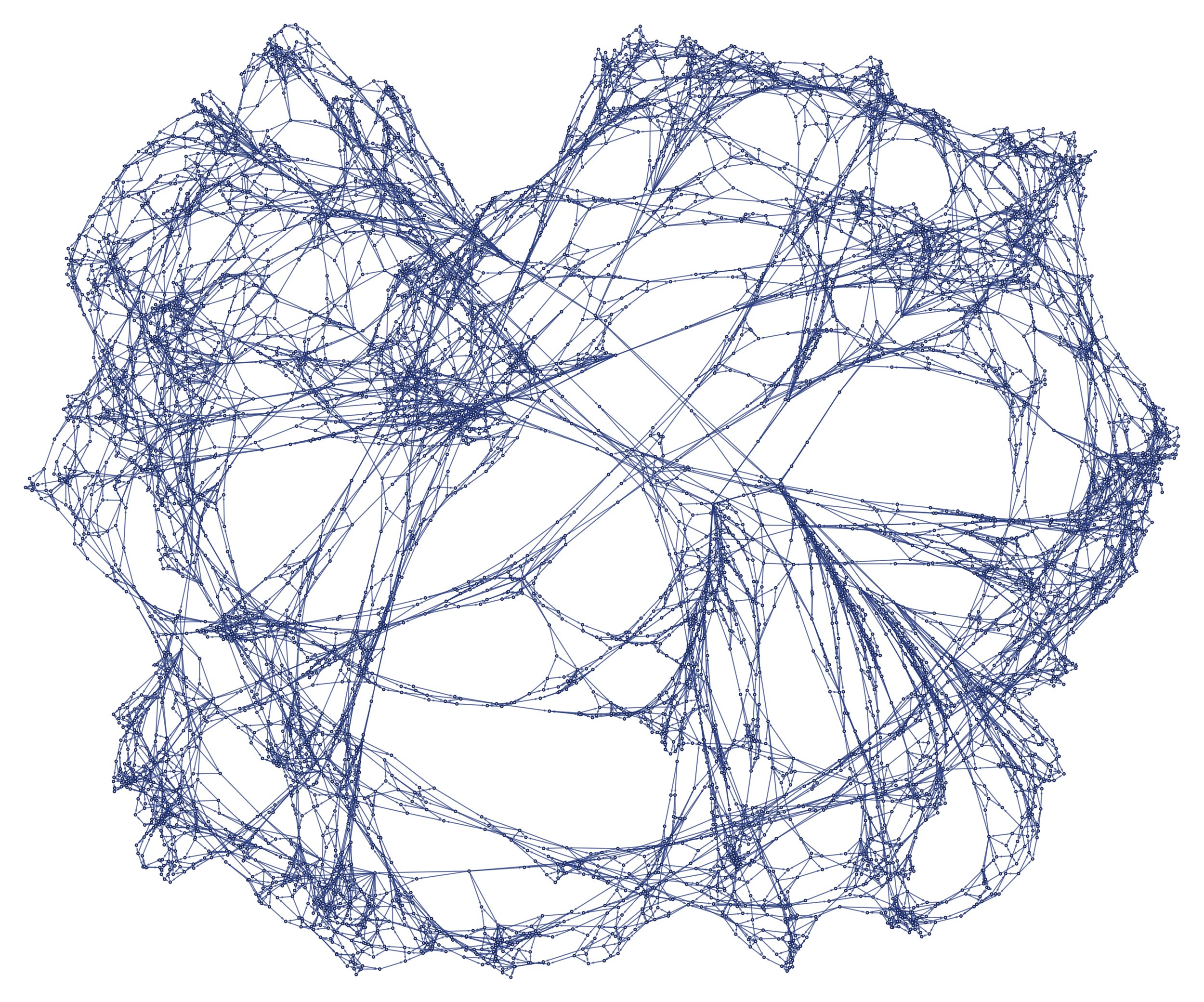

Sixty years later, in today’s cultural landscape, notions of truth have been reduced to personal subjectivity, and public trust has all but disappeared. The situation today is that various sections of America (and the world) have their own separate grip on reality. And even within these various sections are varying constructions of what individuals believe to be true. This dissolution of a cohesive story about reality has also led to individuals only trusting their personally curated realm of information. The atomization and explosion of the internet along with social media has transformed news gathering into a tribal action. Steered by big tech algorithms and evolutionary trip wires, we gravitate towards information that gives us the ‘confirmation dopamine hit’. That is to say we gravitate towards information that seems to confirm what we want to be true; not necessarily what is true.

The consequences of all this are obvious, as conflict and disarray seem to permeate modern reality. For us as human beings, the deeper our disagreements about reality go, the greater the chance those disagreements lead to violence. Think of it this way, a simple disagreement between two people about the score of a baseball game ten years ago will most likely not devolve into deep enmity. Whereas if the same two people were to disagree on religious grounds, on which view of God was ‘correct’; then the prospects for deep seeded hatred and anger greatly increase. I like to think of these deep disagreements as ‘metaphysical disagreements’, or disagreements about the very foundation of reality. The problem with these disagreements is that they are so fundamental, that there can be no common ground. For a person’s metaphysical outlook determines everything from their moral outlook, ethical concerns, epistemology, and approach to logic. Two people with different metaphysical foundations are like two philosophical houses built in different ways, in completely different neighborhoods.

In our current moment we have people who believe there is an omnipotent ruling (and judging) deity in the sky whose human son was Jesus of Nazareth. Not to mention all the other religious conceptions of reality. There are some people who have a completely materialist view about the world we inhabit. These people believe that science and reason are the primary tools to explain the truth about our conscious experience. Others believe the reality we share is determined completely by the racial characteristics of human beings. This view sees the very structure of reality flowing from the color of a person’s skin. While still some people believe in nothing but the nature of power, financial gain, and personal status. This view puts an individual's ego and personal desires at the center of a reality that exists simply for personal exploitation.

There is no real way to square these metaphysical differences. Let alone conflicting beliefs on things like vaccines, global warming, ‘stolen’ elections, or social issues. These secondary beliefs sit on top of, and sometimes flow directly from foundational metaphysical beliefs. In many cases they are products of shortened attention spans and the flood of information that came along for the ride with the digital age. Big tech algorithms create a personal ‘information addiction cocktail’ that is designed to keep users clicking and scrolling. Think of it like a drug dealer tailoring each narcotic dose to stoke the cravings of each individual client. As mentioned earlier, years ago we all watched and read the same news. Now we get personally tailored digital stimulation that we mistake for knowledge and understanding.

The interesting part about all this, is that I’m not sure there is really one place to assign blame for the situation we find ourselves in. I guess one could place much of the blame on the big tech companies; but at the end of the day they were just following the rules of unfettered capitalism. Which means the politicians who allowed such a situation to arise should shoulder responsibility for failing to enact appropriate regulation. I can’t really blame the average citizen; for it’s not their fault digital technology surpassed their ability to use it responsibly. I also can’t really blame them for losing all trust and faith in the news media. Over decades past, the mainstream media has let down the average citizen when it came to things like the Iraq War or the 2008 financial crisis. And in stark contrast to the days of Walter Cronkite, modern media members have become a culturally separated, elite, wealthy part of the ruling class. This has left the mainstream media as a detested (and distrusted) institution alongside Wall Street and major political parties.

It seems like this mess we find ourselves in just kind of happened. A product of forces beyond our control. A product of a reality that started to become atomized in the 1960’s, and only gained complexity and speed in the decades after. Without any fault of their own, many generations entered into a reality devoid of any overarching, truth determining structure. This was mostly due to the weakening of religion’s hold on society, and the decline of blind nationalistic sentiment. So for younger generations today, the truth about reality, and the beliefs that follow, are largely open to personal construction. I’ve used the example before of a vast hall full of millions of Lego pieces. An individual can enter this reality, and put things together however they might like.

On a positive note, this metaphysical ‘free for all’ allows greater room for individuals to chart their own path and decide for themselves what is meaningful and important. Yet as Austrian psychiatrist Viktor Frankl described in his well known book, ‘Man’s Search For Meaning’, the human mind often gravitates towards unhealthy actions when stripped of metaphysical certainty. Frankl notes how when our sense of reality begins to become unmoored, we can be drawn back to certainty by believing what others believe, or believing what we are told to believe. These twin ills of finding meaning through conformist groupthink or following authoritarian propaganda are relevant to our current situation.

The political phenomenon of Donald Trump wouldn’t be possible without the modern status of truth and belief. Trump’s political rise was fueled by his promotion of the racist ‘birther’ conspiracy about the birthplace of former US President Barack Obama. Trump knew the political smear wasn’t true. But he also was cynically savvy enough to realize the power of his lies in an age lacking any coherent truth. He rode the right wing appeal of the birther conspiracy to prominence, and ultimate victory in the Republican Party. He would spew a daily hurricane of falsehoods as he won the presidency, and during the four years after. This would all culminate in violence and turmoil stemming from his biggest lie of all - that the 2020 presidential election was stolen. ‘Trumpism’ became the living embodiment of Viktor Frankl’s warning about the societal pitfalls of groupthink or authoritarianism amid a metaphysical reality that had become deconstructed and dispersed.

American democracy itself was (and is) threatened as a result of the situation we find ourselves in via levels of truth and belief. Yet even if the situation in America was to right itself somehow, the issue would remain a problem at a world, or human species level. I cannot see how as a species, we can truly survive in the long term if we are unable to agree on some basic truth surrounding the nature of reality. Yet I’m also at a loss as to how we could actually arrive at a point where a basic level of agreement was achieved. Will we ever return to the ‘Walter Cronkite world’ where our metaphysical narrative was cohesive and linear? Probably not. But I fear if we keep marching into separate metaphysical trenches, the inevitable result will be more conflict and turmoil. And in an age of nuclear weapons, powerful artificial intelligence, and a warming planet; having constant ‘foundational fights’ about what is really true is a waste of time and a recipe for disaster.